By Sarah Mark,

Washington Post Staff Writer,

Monday, July 17, 2000; Page A01

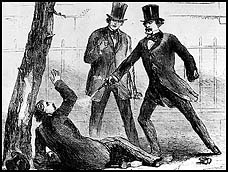

Rep. Daniel E. Sickles kills Philip

Barton Key at Lafayette Square in

1859. A jury later acquitted Sickles of

the shooting. (Harper's Weekly)

Daniel E. Sickles was astonished. When he looked out the window of his mansion at Lafayette Square, the congressman saw his wife's lover signaling her in broad daylight, waving a white handkerchief toward her bedroom window. Enraged, Sickles grabbed two derringers and a revolver, left the house and strode to the other side of the park, where he found his prey, Philip Barton Key.

"Key, you scoundrel. You have dishonored my home," Sickles said, according to witnesses. "You must die."

It was about 2 p.m. Sunday, Feb. 27, 1859, and at least 12 people would witness all or part of the bloody scene between Sickles, a Democratic U.S. representative from New York, and Key, the U.S. attorney for the District.

Sickles fired a gun, the bullet grazing Key. The two men struggled together at the southeast corner of Lafayette Square, right across from the White House, and Key retreated into the street, reached inside his coat and tossed his opera glass at his pursuer. Sickles, who was within 10 feet of Key, fired a bullet that struck Key below the groin, passing through his thigh. Key staggered over to a tree, leaned against it, then fell. He cried, "Don't shoot me!" and "Murder!"

But Sickles pulled the trigger. The gun misfired. Sickles fired again, fatally wounding Key in the chest, according to Nat Brandt in his 1991 book "The Congressman Who Got Away With Murder."

Sickles and Key, both dapper, about 40 years old and part of Washington's social elite, had been friends before Key, the son of Francis Scott Key, started a torrid and rather public love affair with Sickles' young wife, Teresa.

The deadly rivalry that evolved between the two men took place only two years before the Civil War pitted brother against brother. But the slaying had nothing to do with the politics of North vs. South. It had a lot to do with the sometimes violent, frontierlike quality of mid-19th-century Washington.

The capital was a city of contrasts in the decade capped by the slaying case. Elegant balls were held in beautiful houses, yet residents dumped garbage in the alleys, and pigs scavenged freely in the streets. W.W. Corcoran commissioned the design of a splendid gallery for his art collection, yet robbery, assault, thievery and prostitution thrived as the city grew rapidly.

By 1858, a year before the Key slaying, a Senate committee had issued a written report noting that " 'riot and bloodshed are of a daily occurrence. Innocent and unoffending persons are shot, stabbed and otherwise shamefully maltreated, and not infrequently, the offender is not even arrested,' " according to the 1962 book "Washington Village and Capital, 1800-1878," by Constance McLaughlin Green.

And it didn't help that the vast transient population that flooded Washington when Congress was in session "came from states or territories where the border between urbane urban living and rustic rural frontier brushed close," wrote Brandt.

Violence and other vices were not confined to the lower rungs of society. Members of Congress carried guns (many for protection), gambled heavily, visited bordellos and were frequently drunk. " 'While the Democrats and Republicans were in a deadly struggle on the floor of the House over questions involving the destinies of the Union," complained Rep. John Kelly of New York, " . . . the [drunk congressmen] were in the [congressional] bar-room drinking, or on the sofas of the lobby dozing in their cups,' " according to Brandt.

During congressional sessions, fistfights "more than once ended in duels," Green wrote. A congressman shot a waiter in a Washington hotel. On the floor of the Senate, an assailant threatened Thomas Benton of Missouri at gunpoint.

And tensions were high in Congress among some Northerners and Southerners, such as when Preston Brooks of South Carolina savagely caned Charles Sumner of Massachusetts.

To many people in the mid-19th century, a man who seduced another man's wife was asking for it. Today the killing of Key is remembered chiefly because of the 20-day trial in which Sickles was acquitted of murder to the cheers of a crowded courtroom.

Sickles, whose attorneys argued that he went mad because of anguish over the adultery, was the first defendant to use a "temporary insanity" defense in the United States. The trial, which garnered national press attention, made for juicy copy. Sickles' formidable team of lawyers essentially put the dead man on trial.

"Whenever [Key] met her, the whole object of his acquaintance was the gratification of his lust," defense attorney John Graham told the jury, according to an account of the trial published soon after the acquittal. Graham hammered away at Key's "sin," citing passages from the Bible, and arguing that Sickles' "frenzy" was justifiable. The account, by Felix G. Fontaine, called the case "The Washington Tragedy" and sold for 25 cents a copy.

Sickles' suspicions about his wife's infidelity were confirmed by an anonymous note he received a few days before the killing. At the trial, lady's maid Bridget Duffy testified to hearing sobs from the couple the night before the slaying, when Sickles confronted Teresa in an upstairs bedroom.

Despite his distress, Sickles--who also was a lawyer--had the presence of mind to persuade Teresa to write a detailed confession. It was ruled inadmissible in court but nevertheless was printed in the newspapers. In the extraordinarily candid document, Teresa described her numerous rendezvous with Key at a vacant home on 15th Street, a house that Key rented.

"There was a bed in the second story. I did what is usual for a wicked woman to do. . . . I undressed myself. Mr. Key undressed also." She described in detail her garments: "As a general thing, have worn a black and white woollen plaid dress, and beaver hat trimmed with black velvet."

Teresa also confessed to first having met privately with Key in the Sickles mansion. "Mr. Key has kissed me in this house a number of times. I do not deny that we have had connection in this house--in the parlor, on the sofa." She signed it with her maiden name, "Teresa Bagioli."

Teresa was about 20 years old and the beautiful wife of the newly elected congressman when she met the tall, dashing Key at President James Buchanan's inauguration about two years before the slaying. The two subsequently grew friendlier at parties, which her husband often did not attend.

Key had rented the vacant house for their adulterous meetings in a racially mixed area, possibly as a weak attempt at privacy away from their social milieu. The house was only a few minutes' walk from the Sickles home, and it was clear to nearby residents what was going on. Nancy Brown, who lived near the vacant house, testified that Key would enter the home and hang a string attached to an upstairs shutter. The string was a signal to Teresa that he was there.

Key was a scion of a prominent Maryland family. His late father, Francis Scott, was a lawyer who was famous for writing "The Star-Spangled Banner." A widower with four children, Philip Barton Key was a well-known ladies' man, with sad eyes and a languid charm, according to Edgcumb Pinchon in his 1945 book "Dan Sickles: Hero of Gettysburg and 'Yankee King of Spain.' " When Teresa met Key, she was enduring her husband's own infidelities and his frequent absences on political business. Because of the double standard of the era, the well-known fact of Daniel Sickles' affairs made no difference to much of the public.

Key and Teresa soon became passionate about each other. Servants testified at the trial about their liaisons in the parlor of the Sickles home. And Teresa Sickles' coachman, John Thompson, testified that Key (riding his iron-gray horse, Lucifer), would encounter Teresa between almost daily in the afternoon on the street and would frequently enter her carriage.

On several occasions they would visit the Congressional Cemetery on the city's east side or the burying ground at Georgetown. "They would walk down the grounds out of my sight, and be away an hour or an hour-and-a-half," Thompson said, according to the trial report.

The affair must have been particularly galling to Daniel Sickles because of his own friendship with Key, which was launched at a stag whist party in 1857, not long after the Sickles couple moved to Washington. Sickles even interceded with the newly elected Buchanan, who was a friend, to ensure that Key would be reappointed as U.S. attorney.

Ironically, Key's brother, Naval Academy midshipman Daniel Key, had been killed in a duel about 1836 in the village of Bladensburg, just outside Washington. By the time of Barton Key's slaying a quarter-century later, dueling had long been outlawed in the District, but the Bladensburg dueling grounds were still being used by "gentlemen" to settle their differences.

Daniel Sickles' emotional nature was evident throughout the case. Two days before the slaying, he showed the anonymous note about the affair to a friend, congressional clerk George B. Wooldridge, then "put his hands to his head and sobbed in the lobby of the House of Representatives," Wooldridge testified.

After the slaying, Sickles turned himself in at Attorney General Jeremiah Black's house a few blocks away on Franklin Square. Sickles initially was placed in a dark, filthy, vermin-infested cell at the Washington jail at Fourth and G streets, but soon was transferred to the jailer's own office. There Sickles slept on a cot and received meals from home and visits from his 6-year-old daughter, Laura, famous political figures and even his greyhound Dandy, according to Brandt.

Sickles eventually reconciled with his wife, who asked for forgiveness. "God bless you for the mercy and prayers you offer up for me," she wrote in a letter to her husband after the slaying. The press, which had championed his acquittal, criticized him for forgiving her.

Teresa was about 16 (and probably pregnant with their daughter) when she married Sickles in New York 6 1/2 years before the slaying, according to Brandt. Sickles, a New York assemblyman, was twice her age. He had been a longtime friend of her parents, the well-known singing teacher Antonio Bagioli and his wife, Maria.

Sickles was a charismatic man who courted controversy throughout his life and held a succession of significant posts.

After the trial, he served as a controversial Union general during the Civil War (he clashed with another general about troop deployment), as a military governor of the Carolinas after the war and later as U.S. minister to Spain. Teresa took ill and died in 1867 at about the age of 31, and Sickles married a Spanish woman, converted to Catholicism and fathered two more children. (He was rumored to have had a romantic involvement with deposed Queen Isabella II.)

He later became sheriff of New York County, then served in Congress again from 1893 to 1895. He was chairman of the New York Monuments Commission from 1886 to 1912, when he was removed after accusations of embezzlement. He died at 94 in 1914 and was buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

The most telling story about Sickles' gritty character stems from the time his leg was struck by a 12-pound cannonball at Gettysburg during the Civil War. He sent his freshly amputated limb to the new Army Medical Museum in Washington with a visiting card reading "with the compliments of Major General D.E.S."

Two months after the injury, Sickles was back on his horse, and for many years he visited the leg bone on the anniversary of the amputation. It is still on display at the National Museum of Health and Medicine at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Northwest Washington.

Perhaps only a larger-than-life character such as Daniel Sickles could have gotten away with killing his wife's lover in broad daylight. And perhaps it only could have happened when and where it did, in mid-19th-century Washington, a city distracted by its own growing pains and impending hostilities between North and South.

At the time, though, the public regarded the story as a Victorian morality tale of a wronged husband avenging his wife's seduction. Brandt's book cites verses from a song written by an unidentified lyricist:

In the first place this Key he was a false friend, Sickles he thought that on him he'd depend, But the false-hearted villain, his honor betrayed, He took his wife away, and Sickles him he slayed.